Hard Eight (1996)

QFS No. 140 - This is our first QFS selection of a Paul Thomas Anderson film. You know him from all of his great work over the last 25 years but Hard Eight was his first feature. I’ve seen so many of his films but I’ve never seen the first one so this week’s selection attempts to remedy that.

QFS No. 140 - The invitation for May 15, 2024

This is our first QFS selection of a Paul Thomas Anderson film. You know him from all of his great work over the last 25 years but Hard Eight was his first feature. I’ve seen so many of his films but I’ve never seen the first one so this week’s selection addresses that to remedy that shortcoming.

PT Anderson made Hard Eight when he was about 26 years old. What’s almost as infuriating as that is the next year, in 1997, he makes Boogie Nights and then two years later makes Magnolia (1999). By my count, that’s three major motion pictures before he was 30 – including two of those films, Magnolia and Boogie Nights I’d put up there as downright modern auteurist classics. The amount of stars he directed before 30 years old rivals any of the great filmmakers of all time.

Now, whether you enjoy his films or not is a matter of opinion of course. Although he has been Oscar-nominated eleven (11!) times for screenplay (5), directing (3) and best picture (3), he has never won one. This is probably bad luck and circumstance, but it also could be an indication of how people have mixed opinions on PT Anderson’s work.

For example, if you’re a fan of “The Rewatchables” podcast like I am, you probably know that they consider Boogie Nights one of the greatest films ever made. Personally, I enjoyed Magnolia more than Boogie Nights as a film, but even Magnolia is ripe for criticism – frogs and Aimee Mann and whatnot – and is not universally loved. PT Anderson has the young pre-fame filmmaking pedigree of Steven Spielberg in a way, but Anderson’s films are not mainstream nor are they small artistic and abstract explorations of the soul. He’s Martin Scorsese with less benefit of the doubt from critics. Both of them make movies lauded for artistry even though the narrative may not be so clean, but it feels like Scorsese’s long life as a dedicated artist gives him leeway with the public in ways that Anderson may not.

Of course, there is no perfect film devoid of criticism. For me his greatest achievement is There Will Be Blood (2012) one of three of his films nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture along with Phantom Thread (2018) and Licorice Pizza (2022). There Will Be Blood is a singular accomplishment of filmmaking in terms of its scope and its exploration of power, ambition, religion and will. Not to mention the sheer production feat of making a period film with an oil well explosion.

Apparently, PT Anderson’s next film will be released in 2025. All I know is that it’s his first film with Leonardo DiCaprio, which feels like a good fit when making the comparison with Scorsese. Scorsese is undoubtedly one of the greatest filmmakers of the second-half of the 20th Century, and continued on into this one. When we look back in a couple of decades about the greatest filmmakers at the start of the 21st Century, it’s hard to debate PT Anderson including at or near the top of the list. I’m looking forward to finally seeing his first one.

Join me in seeing Hard Eight (1996) and discuss with us!

Reactions and Analyses:

High and Low (1963)

QFS No. 139 - It’s been entirely too long since we’ve selected a Kurosawa film here at Quarantine Film Society. It was way back in July 2020 when we were young and terrified but watched the masterpiece Yojimo (1961, QFS No. 13. The offending parties to this nearly four-year gap have been reassigned to new minor roles within The Society.

QFS No. 139 - The invitation for May 8, 2024

It’s been entirely too long since we’ve selected an Akira Kurosawa film here at Quarantine Film Society. It was way back in July 2020 when we were young and terrified, but watched the masterpiece Yojimo (1961, QFS No. 13). The offending parties to this nearly four-year gap have been reassigned to new minor roles within The Society.

High and Low has been on my list for a long time and I’m a little upset I haven’t seen it yet. Several months ago, I finally saw Ikiru (1952) in the theater at the New Beverly and though it instantly became one of my favorite films, I was simultaneously upset that it had taken so long before watching such a gem.

And so, lo and behold, the New Beverly just screened High and Low to come to my rescue. I was about to select it anyway (seriously – I have notes to prove it!) and so once again the stars align. I have not seen many of Kurosawa’s non-samurai period films, so it’ll be excellent to finally get a chance to see this one.

But also, excellent to watch at home! Then join the discussion of High and Low below if you can!

Reactions and Analyses:

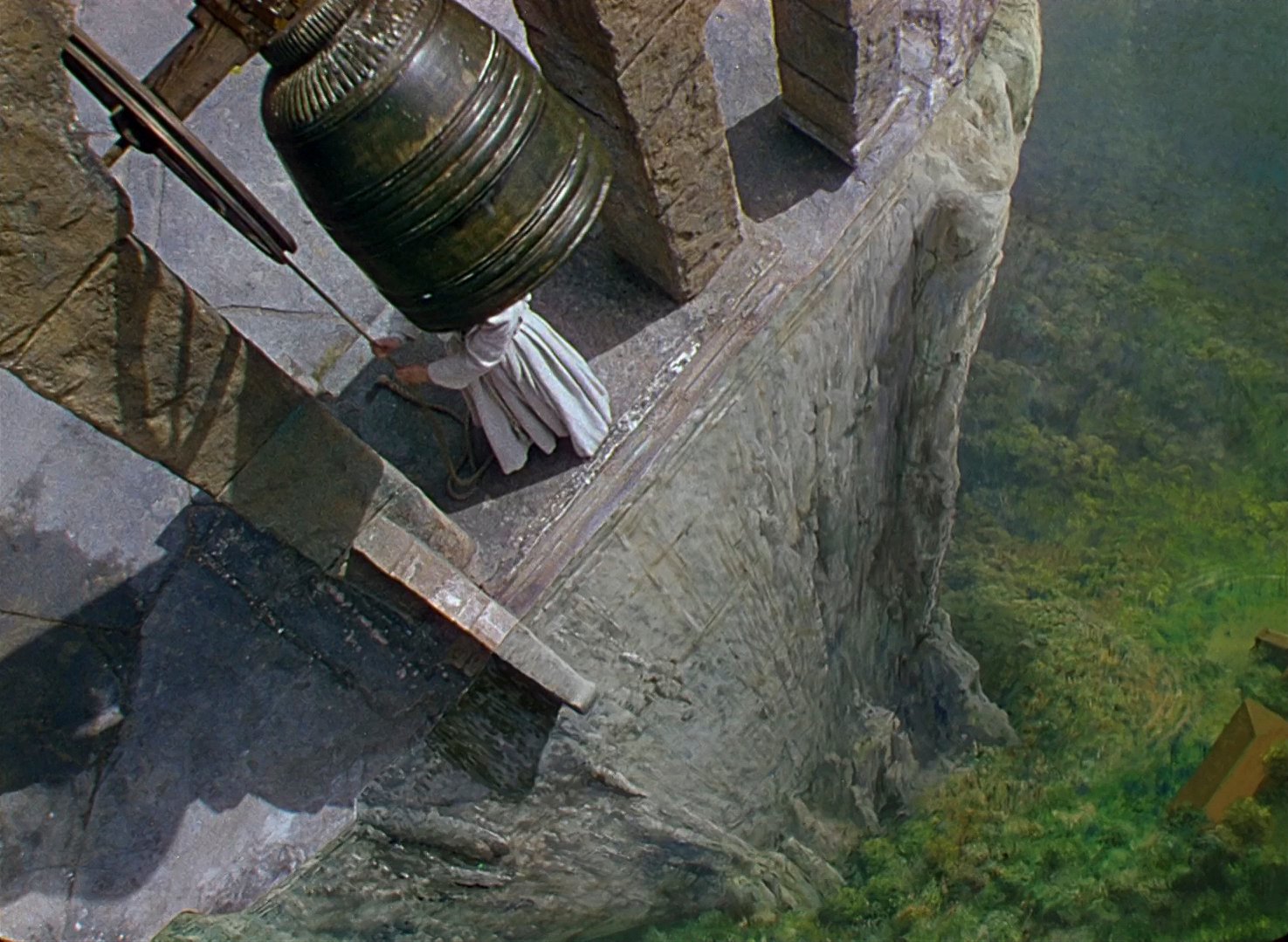

High and Low (1960) has two halves, almost two separate movies. This has long been discussed over the years and by our QFS discussion tackled this as well. But one of our members, a cinematographer, picked up on something I hadn’t noticed – a slight but deliberate change in camera use between the halves.

The first half deals with the kidnapping of Shinichi (Masahiko Shimazu), mistaken for the wealthy child of Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), and Gondo’s decision whether or not to pay a huge sum to this mysterious kidnapper. Shinichi is Aoki’s son, played with excruciating grief and torment by Yutaka Sada. This half of the film takes place all in Gondo’s home, with everyone awaiting the kidnapper’s next call and us as the audience, trying to determine what Gondo will decide.

The camerawork in the first half is composed as if on a stage, with actors blocked in ways where sometimes someone’s back is to us, but their body language speaks volumes. The camera moves, when they happen, are also steady, composed, operated on a gear head for smooth and precise movements.

The second half – the camera is freed. We’re out in the world, on the case, trying to find the kidnapper and also Gondo’s money. It’s likely Kurosawa had seen many of the films of the burgeoning French New Wave movement where the camera is liberated from the tripod and thrust into the dirty, complex world. Kurosawa’s version is still precise and deliberate, but there’s a greater urgency and rapid movement that evokes a handheld style, if not deliberately handheld.

These two styles mimic the change in style, change in movie, change in tone and the change in focus. The drama in the first half of the film is almost entirely internal, just as it is internal in this house. It’s Gondo’s furrowed self-exploration of what to do, whether to give in to the demands and destroy the career and life he’s built for one his personal staff members. It’s the visible anguish on Aoki’s face, at first pleading and then prepared to sacrifice his son in order to save his boss’s livelihood (and, also, his own). There’s his wife Reiko (Kyoko Kagawa) who acts as the moral compass, pleading with Gondo to save the child, that she doesn’t need this home and this wealth.

But is that true? Gondo reminds her that she was born into wealth and has never had to live as he had to growing up so she doesn’t know what she’s talking about. Which then in turn a revelation – that Gondo got a boost early in his career from a dowry from Reiko’s wealthy family.

All of these internal struggles mirror the setting and pace and blocking of the first half perfectly. Kurosawa exhibits his mastery of composition, placing some people in the frame looking towards us and others looking away to enhance their position. Or to have a small sliver of light come through the curtains to bring our focus to a certain place. Kurosawa places Gondo in foreground on the phone, for example, when in the background Aoki anguishes alone and small in the frame. Another moment, when Aoki pleads with Gondo, the two are on opposite sides of the frame – Gondo barely able to look at him.

This deliberate staging allows Kurosawa to play with power dynamics – who is big in the frame, who is small? Who is forced at the edge and who is covered in darkness. It’s brilliant and textbook and requires care to execute. (Of course it doesn’t hurt to have the extraordinary Mifune as one of your chess pieces to play on the board.)

High and Low goes from a story about executive-level business intrigue, to a hostage thriller, to a story exploring social dynamics and issues of wealth, power and poverty before becoming a detective and police procedural with stunning set pieces including the seedy underbelly of 1960s Yokohama.

Kurosawa somehow pulls all of this off without any sense of whiplash or asymmetry. The master clearly at the top of his game is able to balance all of these elements in just about the most seamless way a bifurcated story could be crafted. And he doesn’t abandon elements from first half into the second half – we are reminded of Gondo’s sacrifice when later we see him mowing the lawn. Or when Aoki takes Shinichi back on the path to find the kidnappers’ lair – the detectives catch up with him and Aoki reveals that Gondo told him they won’t need to drive to Gondo’s shoe factory any more, having been forced out as they all knew he would be. We are given glimpses into Gondo’s life changing, even though he barely appears in the second half and we’re more interested in hunt and pursuit of the wrongdoers.

Kurosawa uses this efficiency in his story telling throughout. For example, the bald, sweaty detective Bos’n Taguchi (Kenjiro Ishiyama) – he’s the detective who is rough around the edges but a joking, committed bloodhound. But he’s on the screen so little, how do we know that? Just in a few words, we learn he disdains the wealthy so when Gondo sacrifices we see Bos’n’s admiration. And in behavior – he’s always sweaty and rubbing his head – Kurosawa is a master of tagging a character with a physical tic (see Mifune as “Sanjuro” with the shoulder twitch in Yojimbo, 1961 QFS No. 13). So when this hardened detective breaks down when Aoki and Shinichi reunite, we understand this man and he, in some ways, is a stand in for us as the audience. It’s incredibly moving.

That scene in particular contains another example of Kurosawa’s brilliance. The detectives are in the foreground, their backs to the camera as Aoki runs full speed away from us, towards Shinichi in the distance who runs as well. But the camera stays with the detectives – we see Bos’n holding back tears as he turns towards profile, and Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai) gives the command that kicks off the second half: “For Mr. Gondo’s sake, be bloodhounds!”

And so the second half they’re off, trying to get the kidnapper and recover Gondo’s money.

There are so many points of entry into this film that it’s almost overwhelming to analyze. The bullet train sequence is a masterpiece in suspense. Gondo’s secretary Kwanishi (Tatsuya Mihashi) and his double cross that backfires give us a sense that Gondo is right that his stature is perilous – and Reiko is right ultimately that Gondo’s sacrifice is the correct action ultimately. We also see Kurosawa’s version of a zombie apocalypse film as we explore a heroin den – dreary, seemingly dangerous, the shuffling feet of the addicted clinking on unseen glass vials and bottles. And the plot itself, the suspense and the central question of who is the kidnapper?

Several of the QFS discussion members, myself included, were certain that the other board members of the National Shoe Company arranged for this attempted kidnapping of Gondo’s son. The beginning of the film sets up that premise, which is a great narrative device to send us down that path. But ultimately, it’s a psychopath (but is he a psychopath?), a poor medical intern who looks up at Gondos’ castle above his poor slum. The explanation is that it drove him crazy to see that every day, looking down on them, and that he wanted to teach the man a lesson.

This final scene in the prison between Gondo and Takeuchi (Tsutomu Yamazaki in the only scene where he speaks) gives the kidnapper a chance to explain to Gondo and to us the why. I asked our group the question is this scene necessary. Without it, the scene ends with Mr. and Mrs. Gondo in their emptying house, the auctioneers measuring the furniture for their upcoming auction. For me, that felt like the appropriate conclusion to Gondo’s story and several felt similarly.

However, we would be left wondering why and missing out on any sort of explanation. And though Taekuchi’s motives felt thin – how could he be driven so far when there are probably a couple thousand people in the same situation who saw that same house and lived all around him – who didn’t think kidnap and murder were the solutions. So we’re left with psychosis, something that’s born out by the final images of the film as he’s dragged away, the security gate comes down, and Gondo’s image reflected in the mirror of both lives forever torn.

While I personally would have preferred a stronger rationale for the film’s antagonist, this is a minor story objection to what is one of the greatest films by one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Much of Kurosawa’s work should be essential viewing for filmmakers, but High and Low contains it all – blocking, camerawork, pacing, framing, character development, performance, to name a few. It’s clear to me now that the master’s masterclass for all of us is High and Low.

Wanda (1971)

QFS No. 138 - Woah, what’s that you say? You’ve never heard of Wanda? You uncivilized movie ignoramus. That’s outrageous, well I oughta…

Okay fine. Neither had I.

QFS No. 138 - The invitation for May 1, 2024

I’m sure you all have seen this movie because it’s the 48th Greatest Film of All Time™.

Wanda – according to the oft derided/lauded* British Film Institute Sight and Sound Greatest Movies of All Time List released every ten years – is the 48th Greatest Film of All Time. Forty-eighth! Following a two-way tie between North by Northwest (1959) and Barry Lyndon (1975) at No. 45 and tied at 48 with Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Ordet (1955).

Woah, what’s that you say? You’ve never heard of Wanda? That’s outrageous, well I oughta…

Okay fine. Neither had I.

Wanda falls firmly into the Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, QFS No. 98) territory here – a film from the 1970s that’s highly acclaimed by critics and filmmakers and one I have never heard of. (Not stylistically, just in terms of obscurity… for me at least.) I do feel some measure of shame for not knowing about both Wanda and of course Jeanne Dielman from before. So here we go again, firming up our film nerd cred by watching and discussing Wanda as a film and of course whether there are only 47 greater films ever made than it. I know very little about this movie but what I do know is that it is significantly shorter than Jeanne Dielman.

For those of you keeping score at home, this happens to be our tenth selection from the BFI top 100 list. We’ve previously selected No. 1 Jeanne Dielman, No. 5 In the Mood for Love (2000, QFS No. 105), No. 11 Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927, QFS No. 104), No. 30 Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019, QFS No. 114), No. 43 Stalker (1979, QFS No. 25), No. 60 Daughters of the Dust (1991, QFS No. 18), No. 67 The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), No. 72 L’Avventura (1960, QFS No. 116), and No. 95 A Man Escaped (1956, QFS No. 9).

I have seen 60 films in the Top 100 and yes, I just them up counted now. Am I proud of this or a little concerned? I’d say both. Looking forward to knocking No. 48 off the list! Watch Wanda and return here to discuss!

*I both laud and deride the list routinely.

Reactions and Analyses:

It’s hard to watch Wanda and separate the narrative from the craft. The story, though thin on a driving narrative, is still compelling. And the reason to keep watching is Wanda (Barbara Loden), seeing what happens to her as she drifts through her life. The movie is also about how Loden made it and what that evokes in us as a viewer. This is true for many films to some extent – the how did they do that idea – but there’s something different about the “how” with Wanda and it in some ways fleshes out the “why.”

Shot mostly on 16mm reversal stock – which is cheaper but less forgiving than negative film and more in line with budget-strapped documentarians of the day – Wanda, though restored, retains the grainy immediacy of the shooting format. Which makes it feel like a time piece. Stores that no longer exist populate the world (Woolworths and Korvette), the clothes, the rampant smoking, the cars that are easy to break into and hotwire. Although it’s not a documentary and it’s not New Wave, it has a feeling of being a loose and free portrait of a time, place and character where we’re experiencing the world with Wanda because we experience almost the entire film through her perspective.

Our group had a very mixed set of reactions to the film. Wanda gives so little information that the viewer pieces backstory and character motivation together with the clues that are in there throughout. Motivation is a tricky word because … is there motivation? Is Wanda motivated at all? She’s the biggest enigma of the film. Her expression and her emotions are minimal. She’s in court and does the opposite what we’d expect – she doesn’t fight for custody of her children at all. She can’t care for them but also doesn’t seem to even acknowledge them. The children, shockingly, don’t acknowledge her at all.

This speaks volumes and breaks with audience expectations of how a woman, a mother, would behave when around her children. The children perhaps no longer know Wanda as their mother at all.

When I saw this scene, I felt I knew Wanda or at least understood her backstory. She felt like people I know who I grew up with in the Midwest and so I extrapolated what I felt I knew about her. She is from a place and time where women aren’t getting a great education and are likely expected to marry at a young age. She’s attractive, so I imagined she got by on her looks, married young, had children young, and suffers from depression – or at least this sense that she never had direction in her life.

And true enough, the film starts to bear this out. Wanda does in fact get by on her looks – she’s robbed, has no money, but sleeps with a man who’s paid for her drink and then abandons her at an ice cream stand (who also takes pity on her and gives her an ice cream cone, unbidden). She’s directionless and just pulled along by whatever happens to her, getting swept up with a two-bit crook Mr. Dennis (Michael Higgins) and ends up being his accomplice (but it’s not clear she really wants to?). No one shows her any kindness without it being transactional - for sex, usually - except the guy with the ice cream cone and a brief moment when Mr. Higgins tells her she did good in their taking of hostages. The smallest of smiles crosses Wanda’s face and you get the sense that nobody has given her an earnest compliment in a long time, or maybe ever.

Wanda does push back at one point, vomiting from nerves before the ill-conceived heist and saying she doesn’t want to go through with it. It’s one of two times she takes real action and shows agency. (Of course, she gives in and goes through with the bank robbery anyway.) The second time is near the end of the film when the airborne officer attempts to rape her in his car and she actually fights back and escapes.

The passivity and the narrative ambiguity proved to be too much for several of the QFS members. For me, I was taken along with the filmmaking and the storytelling but I definitely can understand how frustrating Wanda could be as a character. What is motivating her? What is she living for or striving for? Nothing? It must be nothing.

The filmmaking, however, is pretty remarkable. As mentioned earlier, this is one of the cases where I find it’s hard to separate the film from the filmmaking, or the feat of how they made the film. It has that lean, free-camera feeling of an expert filmmaker, not a first-timer with a crew of … four!

For example – the early shot in the film, when Wanda leaves what has to be one of the bleakest houses ever portrayed in cinema as it’s immediately adjacent to a coal strip mine. Wearing light colors, she walks through a black landscape, coal all around, the camera feels like it’s a mile away and she’s very tiny in the frame. The shot continues for a long time. Too long, contemporary audiences complained. To which she explained in an interview (as retold in Current), “I wanted to show that it took a long time to get from there to there.”

That’s very telling, and also illustrative of Loden as an artist. She made choices in a film that seems “real” and that we’re watching a real person drift through life. It’s a real tragedy that Loden never made a movie and died a decade later. Her follow up to Wanda would’ve been something very special. The filmmaking of Wanda should be taught to directors just starting out who use their own moxie to pull off something meaningful.

The driving sequences should be necessary film references for any filmmakers shooting from or with a car. Loden has shots looking through the front windshield onto the drivers – which means, given her limited budget, that they had the camera operator strapped to the hood of a moving car. The shots are so lovely for what is probably one of the most awkward road trips ever filmed. During that trip, the camera is in the passenger seat (sometimes the driver’s seat!) looking right at Mr. Higgins or Wanda, and it feels like we’re on the trip with them. But the driving sequence that’s most riveting is the attempted hostage taking and bank heist. The interplay between the two cars, the movement, the camera moves inside the car from Mr. Higgins’ watch to his face for example – these are extraordinary. There is so much dynamism in the sequence, so much tension – especially when Wanda is pulled over for making an illegal U-turn – that it suggests a much more experienced director at the helm than someone making their first film.

Variety of shots while driving, expertly done by Loden and her cinematographer/entire camera crew Nicholas T Proferes.

Wanda evokes Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973) – a film that comes out only three years later. (I made a joke in our discussion that this was a much sadder film given the petty and incompetent thief and should be called Sadlands. It got very few laughs but it’s hard to tell on Zoom sometimes, right? Right?) Similarly in the two films there’s the crime, the listless, emotionally detached lead female protagonists who are carried through the story by awful men, taking place in a part of the country that rarely is portrayed authentically on the screen. I have no way of proving the connection, but I discovered that Loden gave a Harold Lloyd Master Seminar at the American Film Institute in 1971 – a time when Malick would’ve been in the audience. I have a theory that Malick was inspired by Loden and what she was able to accomplish on virtually no money and no crew. (Though Malick had young stars, more money and more crew than Loden - but not a lot more.)

Wanda (1970) on the left and Badlands (1973) on the right. I’m sure Loden’s talk at AFI in 1971 helped inspire Terrence Malick to make his first movie, too. (More like “sadlands,” am I right?) I’m compelled to say that I’m a proud alum of the AFI Conservatory and am trying to will this connection into being if it isn’t totally true.

For a film with an inscrutable lead character – or at least one whose motivation can be debated – the most confounding part is the ending. The film concludes on a grainy freeze frame of Wanda, seeking refuge in a bar after nearly being raped (again). Everyone around her is having a good time and laughing it up while she sits and others buy her drinks and food.

But what will happen to her? Will she continue on as she has been? She’s gone through no personal epiphanies, no great character arc. We have no reason to believe that Wanda is going to change. And perhaps this is the lasting idea that Loden wants to leave us with in this image. The world is all having a good time around her, swirling, living life. But she is stuck – literally, since it’s a still image – in her place, dependent upon the goodwill of others and unable to (incapable of?) change. Perhaps it’s a stretch, but the film does begin the way it started – there is no explanation, there is only interpretation.

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

QFS No. 137 - For our four-year anniversary of QFS, we decided to select an epic by the great David Lean. Yes, it took us four years to get to a David Lean film, and for the most part it’s because I’ve seen most of the epic classic ones. Lawrence of Arabia (1962) remains one of my favorite films of all time and we could easily have selected it to commemorate our four years of watching and talking about movies. But instead, I picked what is my second favorite Lean film, The Bridge on the River Kwai.

QFS No. 137 - The invitation for April 24, 2024

Happy Fourth Anniversary!

For our four-year anniversary of the Quarantine Film Society, we decided to select an epic by the great David Lean. Yes, it took us four years to get to a David Lean film, and for the most part it’s because I’ve seen most of the epic classic ones. Lawrence of Arabia (1962) remains one of my favorite films of all time and we could easily have selected it to commemorate our four years of watching and talking about movies.

But instead, I picked what is my second favorite Lean film, The Bridge on the River Kwai. I’ve seen it in the theater once and probably half a dozen times in total. (I have somehow managed to watch Lawrence of Arabia about six times in the theater over the last 20 years in LA, a personal achievement of which I'm quite proud.)

One of the things I love about David Lean and why I love his filmmaking is that he makes the epic personal. He crafts giant films on huge tapestries during times of war or conflict – but they are, at their core, character dramas. Lawrence of Arabia is, among other things, an exploration of a man’s identity, of living in between two realities, all set against the World War I proxy conflicts between Turkey and the Arabian kingdoms. A Passage to India (1984) examines race, imperialistic hierarchy, and tolerance during the British Raj rule of India. Doctor Zhivago (1965) is set during the Russian Civil War and beyond but concerns itself mainly with the love story between the two protagonists.

Set during World War II in Burma, The Bridge on the River Kwai is a fascinating tale of duty, of an almost sacred commitment to a task. The film questions whether that task is moral or not. We will discuss this further when we chat about the film, but I’ve always be interested in what is known in Hindu philosophy as dharma – one’s sacred duty – and The Bridge on the River Kwai manages the best portrayal of the concept I’ve come across in Western cinema through Alec Guiness’ character. Again, here the film is not about the war. But war surrounds the story. The epic is backdrop for the personal.

Speaking of epic, just a brief reflection on pulling off a four-year run of Quarantine Film Society. Sure, “pulling off” wasn’t really all that much doing. Simply (a) repeated unemployment of yours truly, (b) stubbornness, (c) an eagerness to write mini-film essays nearly weekly and (d) have at hand a bunch of maniacs willing to watch a film and get on an online video phone to talk about it.

These four years I’ve watched more movies than perhaps any other four year stretch of my life except perhaps for college. I’ve greatly expanded my working knowledge of the craft of cinema, American film history of the 20th Century, and have gained a greater appreciation of film as an art form – in that it can be interpreted less like a sentence in a book and more like a painting in a gallery.

For all of this, I thank you. I hope to keep this up for as long as I can. Join me to discuss The Bridge on the River Kwai as kick off our next four years of world cinema domination.

Reactions and Analyses:

Who is the antagonist in The Bridge on the River Kwai? For a film that has a lot of traditional action elements, it is not an action film in the classic sense. Or a war film in the classic sense, for that matter.

This question, though, of who is the antagonist or “the bad guy” is an interesting one and was quickly brought up by one member of the group. He argues that it’s actually Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness). He’s a maniacal man hellbent on living up to his own moral code, to the point of collaborating with who is his enemy.

This is a fascinating take on the film and several QFS members felt similarly. Nicholson, is governed by a code and cannot waver from it. If anything, his counterpart Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), who runs a prison work camp, is downright reasonable by comparison. Nicholson nearly sacrifices not only himself but his officers on principle. He nearly completely and totally collaborates with the enemy, very nearly (inadvertently) foiling the covert mission by his own government.

Consequently, several QFS members felt that this makes him a merciless sociopath. Sure, I can see that. But also, I’ve always seen him as totally and completely tied to his duty. As I wrote in the invitation to The Bridge on the River Kwai, for me Nicholson evokes the philosophical concept of dharma – which can be translated to spiritual duty, a duty that’s beyond mere obligation but something that’s deep inside of you that you have no choice but to fulfill. There are characters who appear in Hindu mythology who embody the concept, and at times they are unable to do anything other than their duty. They are, as I’ve heard referenced “bound to their dharma.” Rama from the epic The Ramayana has to obey his elders, his father, even when doing so triggers off a curse that leads to his father’s death. (There’s more to it than that but for simplicity’s sake, I’m boiling it down.)

Also, in the other Hindu epic The Mahabharata, the warrior prince Arjuna is on the eve of battle against his family and is paralyzed by inaction. Krishna, who is Lord Vishnu incarnate on earth, guides Arjuna through this crisis by reminding him that his duty is as a warrior for his people, and a warrior fights. Even when it’s going to be against cousins and uncles who he knows and loves – because he is on the side of righteousness. (Again, this is massively oversimplifying the Bhagavad Gita but go with me here.)

Now, I’ve always felt that Nicholson embodies this concept better than almost any character I’ve seen in a Western film that isn’t inspired by Eastern philosophy directly. And I still feel that way, but I noticed something different this time that should’ve been obvious to me before – this is an antiwar film. Nearly every war film is at its core an antiwar film. But The Bridge on the River Kwai is perhaps even darker. It’s not only addressing the cruelty of war, it criticizes the very necessity of war – and of the British Empire. The bridge is more than a bridge - it’s a symbol of colonialization and empire.

QFS members pointed out the arrogance of Nicholson, claiming their British engineers are superior intellectually to the Japanese ones, their workmanship and organization the model of the world. Some in our group couldn’t really tolerate that, which is totally valid. But this arrogance is entirely David Lean’s point. It’s this arrogance, this expressed superiority – that it’s all nonsense. And, in the end, futile and destructive. Like the British Empire, they’ve gone in with what they believe to be good intentions, but leave behind destruction, ruin, and death in their wake.

Or “Madness,” as the medic Major Clipton (James Donald) says in the last line of the film. And after the destruction, Lean leaves us with a final shot, an aerial pullback, wide, from the sky, with a jaunty British military tune. This is not accidental, and it’s an acerbic, biting final blow against the British. He could’ve chosen somber or desolate music. But the final tune has the flavor of cynical sarcasm to it.

And yet, it’s Nicholson, bound by dharma, who must build the bridge and can only do so the best he can. He can’t even comprehend what others are telling him when they say to not build it so well. There are many telling exchanges in the film, but this one to me stands out as emblematic of what I mean:

Major Clipton: The fact is, what we're doing could be construed as - forgive me, sir - collaboration with the enemy. Perhaps even as treasonable activity.

Colonel Nicholson: Are you alright, Clipton? We're prisoners of war, we haven't the right to refuse work.

Major Clipton: I understand that, sir. But... must we work so well? Must we build them a better bridge than they could have built for themselves?

Colonel Nicholson: If you had to operate on Saito, would you do your job or would you let him die? Would you prefer to see this battalion disintegrate in idleness? Would you have it said that our chaps can't do a proper job? Don't you realize how important it is to show these people that they can't break us, in body or in spirit? Take a good look, Clipton. One day the war will be over, and I hope that the people who use this bridge in years to come will remember how it was built, and who built it. Not a gang of slaves, but soldiers! British soldiers, Clipton, even in captivity.

The incredible build up is all worth it – the long film, the (perhaps) extraneous William Holden (as “Shears”) sequences, the near suicide of Hayakawa – it is all worth it for that moment when Nicholson discovers that it’s his fellow British soldiers who are trying to blow up the bridge. As if awaked from a trans, Nicholson says What have I done? Truly one of the greatest epiphanies ever filmed, both in terms of performance and payoff. Nicholson remembers that the bridge was his duty, but there was a greater one and it was for the British Army.

A final note – I thought I had this film figured out. It has remained in my memory as one of my formative movies. But rewatching it and discussing with the QFS group has introduced even more complexity into the story and the themes. Once again, the mark of a truly great work of art and craft by one of the masters of the medium.

Ace in the Hole (1951)

QFS No. 136 - I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

QFS No. 136 - The invitation for March 27, 2024

This is our second Quarantine Film Society selection by the great Billy Wilder, after having seen one of his earlier films The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) a couple years ago. Ace in the Hole (1951) has been on my to-see list for some time, so I’m very much looking forward to it.

I was tempted to select a Wilder film I’ve already seen because they are so rewatchable. And I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films - Some Like it Hot (1959), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Apartment (1960), Double Indemnity (1944) are such terrific classics - but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

Reactions and Analyses:

One of the most surprising aspects of Ace in the Hole (1951) is that it’s from 1951 and not 1971. There’s an expectation for many of the post-World War II American films, that they have a Capra-esque quality. A happy ending or at least one that’s, at best, ambiguous or a qualified victory for the protagonist.

A happy ending Ace in the Hole certainly does not have. One of our group members highlighted a shot at the end of the movie, where the crowds have recently left and all that remains is Leo’s father near a sign that reads “Proceeds go to Leo Minosa Rescue Fund.”

It’s a shot that speaks to the fickle nature of the crowd, the spectacle over, and all that remains is the detritus of the carnival and a family in ruin. Leo (Richard Benedict) has died. His wife Lorraine (Jan Sterling) has departed with the masses, just as she intended to early on before Tatum (Kirk Douglas) convinces her that her fortunes will change soon. And Tatum, having used Leo and keeping him trapped longer than necessary in order for him to reap the benefits of the sensational story going viral before “going viral” was a term, also dies. But not before a final act of almost valor.

The 1970s – coming on the heels of New Wave moments throughout Europe which in turn came on the heels of Post WWII neorealism – featured a generation of filmmakers who were raised by people who had witnessed the horrors of humanity and understood that real life had no clean happy endings. Obviously, this is an overgeneralization but the trends are clear to see from the films that came to life in this era in the second half of the 20th Century.

With its social commentary on human nature and their attraction to spectacle, the media’s role in fanning the flames of that human nature, and a non-Hollywood ending Ace in the Hole feels like an independent film from the 1970s and not a studio release from twenty years earlier. You can easily see a throughline between this and Network (1976), a film whose very essence is an analysis of media, entertainment and sensationalism. The cynicism in Ace in the Hole feels uncommon for the 1950s, with the Cold War in its infancy and the Allies victory in World War II fresh in people’s minds. The fact that it’s Billy Wilder and that the film is twenty years before its time, in some respect, is perhaps why I’m so drawn to it now and why it has been rediscovered as an overlooked classic of the time.

Tatum says early in the film, “You pick up the paper, you read about 84 men or 284, or a million men, like in a Chinese famine. You read it, but it doesn't say with you. One man's different, you want to know all about him. That's human interest.” Tatum, as an anti-hero, displays a deep understanding of that human nature throughout Ace in the Hole. Sheriff Kretzer (Ray Teal) hates him but Tatum turns him around and knows what the sheriff most wants – to be seen as powerful and important. Tatum tells Sherrif Kretzer how he will promote the sheriff as the man most determined to save Leo and in exchange Tatum gets exclusive access to the mine and the metaphoric gold inside. He convinces Lorraine to stay in town and play the grieving wife because it will make her a star and make all of them money. Tatum is a devious genius and he almost pulls it off.

“Almost” is the operative word. His gamble has proven too costly and Leo dies. And here’s one of our primary debates happened in our QFS discussion group. In the end, does Tatum feel guilty? Is that what drives him at the end? He’s clearly devastated by Leo’s death – but is it because it ruins his own chance at stardom and the heights of journalistic fame? Or is it because he’s come to terms with the fact that he’s Leo’s “murderer,” that he directly caused Leo’s death and consequently has a moment of clarity?

Several in the group believed that Tatum has no real remorse. Sure, he didn’t want Leo to die but he also knew that it meant the end of his own life. Others believed that he did in fact feel remorse and you can see it by his solitary act of bringing in the priest to comfort Leo for his final moments. Then, Tatum literally shouts from the mountaintop to tell everyone that Leo is dead and the carnival should go home. If he was truly in for all of this glory himself, he would’ve let Leo die quietly and had the “scoop” on Leo’s final minutes. (“Scoop” in quotes because Leo is the one creating this scoop.)

(Above sequence:) Tatum shouts from hilltop that Leo is dead. Is this the guilt-ridden face of a man full of remorse?

For me, personally, I think he did feel a measure of remorse and guilt but too little too late. And perhaps that’s why he doesn’t seek medical attention after Lorraine stabs him – he knows it’s his penance. He has to now suffer as he’s caused Leo’s suffering for his own gain. Perhaps explains why he accepts this pain without seeking amelioration or offering complaint, but it’s left (deliberately?) ambiguous.

People in our group brought up the cynicism but for me – and I said this early in our discussion – the film didn’t strike me that it was overtly cynical. And that probably says more about me or the time in which I live in now. For the 1950s, sure, the film is more cynical about human nature than popular culture portrayed. But we’ve now lived 75 years or so since then and seen the world revolve around capitalism, social media, hype, and the classically American propensity of squeezing money from every corner of human life. GoFundMe campaigns and “tribute” songs to raise money are the a logical extension of the funds to save Leo in the cave, the altruistic flipside of tragic spectacle.

And Leo – even the most “sympathetic” character in the film – is a grave robber of Native American artifacts! The person we’re cheering for to survive has, himself, stated that he’s probably cursed by the old spirits for robbing one too many times the burial sites of the indigenous of New Mexico. (Not to mention the studio so disliked the film that after its initial release they pulled it and remaned it “The Big Carnival” because people, you see, like carnivals so they might think it’s a fun movie! Talk about cynicism.) So it’s fair to say Ace in the Hole does have loads of cynicism – on screen and off – even though that’s not what first struck me.

The story is rife with plot holes as pointed out by the group, including the biggest one – why couldn’t Lorraine go down there to talk to Leo? It’s true – once Tatum goes down there frequently and it’s seemingly now safe to talk to Leo, then why can’t people who love him do that, like his parents? Also, is it believable that Tatum would suffer a stomach wound like that for so long? Only if he believes it’s a moral punishment.

And there’s this question – did Tatum ultimately win? He, too, is stuck in a hole – both he and Leo are in a hole together, one actual and one metaphoric. Both are counting on the other to extract them from their personal holes, but both die together. Tatum’s goal was to get back on top, become famous and return to New York. And while he doesn’t make it to New York and out of Albuquerque physically, he has become famous – people are cheering for him, the radio broadcast wants his exclusive thoughts. He is, for a moment, atop the world.

But it’s all fleeting, like the masses who come overnight and leave the next day as the tragedy ends. Ultimately, Tatum will become infamous and perhaps that’s victory enough – especially if you’re a cynic.

20 Days in Mariupol (2023)

QFS No. 135- Long time QFS members know that we rarely select documentary films due to a long-standing bias against them within the ranks of our QFS Council of Excellence. This is only our third documentary selection.

QFS No. 135 - The invitation for March 13, 2024

Long time QFS members know that we rarely select documentary films due to a long-standing bias against them within the ranks of our QFS Council of Excellence. This is only our third documentary selection. The other two – Honeyland (2019, QFS No. 5) and Flee (2021, QFS No. 69) were also both nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards, with Honeyland taking the prize in the 2020 Covid year Oscars. Flee did not win, but was the first film ever to be nominated for both Best Documentary Feature and Best Animated Feature – a feat which is still pretty astonishing. It remains one of my personal favorite films of the decade.

What both those films had in common were that although documentary films, they felt as if they were scripted narrative features. Honeyland followed an old lady in Macedonia harvesting honey the old-fashioned way as if it was a scripted movie, in a sense. Flee also had a scripted animated feature film feel – both because of the story of the protagonist’s life and the masterful manner in which it was told.

Which brings us to 20 Days in Mariupol (2023) – a documentary which will likely have a similar narrative action film feeling. The story was introduced to me last year by my brother who sent me this link to an Associated Press story by and about AP journalists trapped in Ukraine as the Russians invaded. They had been reporting from the battlefield and soon discovered that they were also being hunted. As most of you know, my brother is a journalist and he first learned of this incredible story while serving on a committee that selected these reporters for an award. Of course upon reading the story myself, I immediately knew this was a movie and started to look into whether the rights were available. Little did I know that the documentary was being finalized with footage from the frontlines by the journalists themselves. A movie, in some fashion, was already in the works.

The story is incredible and let me give you the lede right here: “The Russians were hunting us down. They had a list of names, including ours, and they were closing in.”

If that’s not the way to begin a great story – on screen or in print or otherwise – then I don’t know what is. The fact that it’s also a true story and one that we can watch, well I think we ought to do that.

Reactions and Analyses:

What can a documentary do that a scripted feature film cannot? This is one of the questions that went through my mind as I watched 20 Days in Mariupol (2023) and one of the first aspects of the film we discussed. In a narrative film, even a bleak film featuring war, desperation, doom and destruction all around – you would be hard pressed to find a movie that didn’t have some inkling of hope. Some path to escape, at least, if not victory outright for the protagonist.

In a documentary, however, there’s no expectation that you will receive that olive branch or lifeline from the filmmaker. The film can be as relentless as it needs to be because this is real. In a feature film, the filmmakers would (rightly?) be trashed for putting the audience through something relentlessly harrowing. In a documentary, you can turn that feeling into something like a duty to watch it. Because providing witness is what the filmmakers are hoping for in showcasing it for an audience.

One in our group put it that way – it felt like our duty to watch 20 Days in Mariupol. In part because the filmmaker-journalists made it their mission to make sure the world knew what was happening in Mariupol. Going into this film, I had some knowledge of what the filmmakers went through, having read the Associated Press reporting and also the story of the filmmakers being personally targeted by the Russian troops. I expected the filmmakers to include themselves in the storytelling, much in the way The Cove (2009) did – also an Oscar winner for Best Documentary Feature – as someone in the QFS group brought up that parallel.

Refreshingly, the filmmakers of 20 Days in Mariupol did not give in to making the film about themselves beyond what was necessary to tell the story. Although Mstyslav Chernov’s voice guides us in voiceover, the camera is never turned inward. He reflects on occasion about being Ukrainian and there are artistic vignettes of a hand covered in sand and images of his children playing in safety, for example. But they are, thankfully, very few and used at just the right times and just the right ways to break up the constant movement and bloodshed we witness on screen.

To that point, another in our group brought up the moments where the filmmaker sits down, camera still rolling, and we see a hallway sideways or the ground, not focused on anything in particular. The filmmaker catches his breath, taking in the horror and pausing from showing more if it. The moments are needed relief and are a fascinating way of involving the filmmaker in the story in a subtle way. An editor and director could have easily cut those parts out as they don’t advance the “story” or any narrative, but keeping those moments in both help to humanize our filmmaker guides through the film but also to emphasize that we are in this with them – experiencing this with them.

One member of the group mentioned that we never see the filmmaker’s face (until the very end). And yet, we are riveted – we want him to survive. He is us. In that extraordinary action sequence when they have to escape the occupied city with a Ukrainian special strike force, the filmmaking is as good as any you’ll see in a modern war film or a video game. We’re running, we see the soldier in front of us talking when paused around a corner, we dive when an airplane screams overhead. We’re on the edge of our seat, wondering how the filmmaker will survive. And yet – we’ve never seen his face.

That’s a pretty remarkable feat. Perhaps it’s because it is us. We are looking and experiencing the world with this filmmaker and exclusively through his eyes throughout – which is perhaps another thing documentary does that a feature film wouldn’t be able to get away with necessarily. Not seeing the protagonist at all and playing the film entirely through point of view is a hallmark of “documentary style” but often you see clever ways a narrative filmmaker will at least give us a glimpse of the person holding the fictitious camera. But in the documentary, we don’t see the person holding the camera, favoring instead the horror but not in a gratuitous way – it’s real, seen how a person would. At times directly, at times looking away, searching for something else but drawn back to the calamity. The blood, the babies dying or living, the people grieving the death of a child or other family member. We experience it in what feels like real time through the filmmaker’s eyes.

And finally – since this is such a recent war, one still going on, there are so many elements that make it feel truly “modern.” There’s the mission to get internet. Seeing the dozens of power strips so people can charge their phones just to use them as flashlights. The familiar buildings (e.g. Crossfit gym!) being used as shelters or bombed out malls. And then, the entire social media storyline in which the Russians accuse the reporters of faking the bombed out maternity ward and using crisis actors. “Fake news,” if you will. History isn’t just written by the victors, it’s being written in real time – as one of our QFSers put it.

In Chernov’s Academy Award just a few days ago, he said:

“But I can't change history, I can't change the past, but we are all together, you and I, we are among the most talented people in the world. We can make sure that history is corrected, that the truth prevails. And so that the people of Mariupol who died and those who gave their lives will never be forgotten. Because cinema shapes memories, and memories shape history."

Chernov’s use of footage he shot which then later appears as news footage in television programs around the world is incredibly effective in so many ways, but in one way in particular. It reminds us that one of the main driving narrative thrusts of the film is we need to get the story to the world. To prove it happened and so no one forgets. The fact that it was real, that it was a documentary, makes it more urgent for the filmmakers to share it and for the world’s eyes to see it. They got it out to the world and we’ve seen it. We were witness and it was, indeed, a duty to help shape memories and history.

Past Lives (2023)

QFS No. 134 - What I know about this film approaches zero. I do know it’s from South Korea and that it’s Celine Song’s first film after being a staff writer on a major Amazon series. So, you know – pretty amazing, that!

QFS No. 134 - The invitation for February 28, 2024

What I know about this film approaches zero. I do know it’s (partly) from South Korea and that it’s Celine Song’s first film after being a staff writer on a major Amazon series. So, you know – pretty amazing, that!

But I’ve deliberately kept myself away from knowledge of the plot and was looking forward to seeing the film. This is our second selection from South Korea, the other being Bong-Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder (2003, QFS No. 112), and many more remain on my to-watch list. The South Korean film industry just keeps blasting home runs all over the place.

Join us this week if you can!

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a shot in Past Lives (2023) that essentially tells the premise of the film in one frame. It’s early on, Na Young says goodbye to Hae Sung because her family is immigrating from South Korea. The goodbye is curt and without over-wrought emotion because, well, they’re adolescents.

Then they each walk towards their own homes – Na Young upwards on the right of the frame and Hae Sung on the left, more or less straight, away from us. This image defines, in some ways, their trajectories. It’s simple and straightforward but clear. And it definitely sets a course for the split in their lives.

When I first selected Past Lives, knowing very little about the film besides its accolades and that it’s Oscar nominated for Best Picture, I assumed this was a South Korean film. And after having seen it, I can say that it’s very much an American film, an immigrant’s tale. This splitting or fracturing of a life in divergent storylines. It could’ve been told from my parents’ perspective leaving India in the 1970s.

I brought this up in our QFS discussion and the others pointed out that this is not just an immigrant’s tale – this is the story of anyone who is forced to split from their home at a young age and has that fondness, that nostalgic remembrance, and that powerlessness to stop that fracturing the familiar. The fact that this is also true and valid illustrates how universal and accessible the story is.

Past Lives makes an argument for the simple film told with tenderness but with just the right amount of layering. The Korean concept of “in-yun” – the layers of interaction between throughout past lives – feels deliberate beyond how it’s used to describe the relationship between Hae Sung (Teo Yoo) and Na Young/Nora (Greta Lee). Perhaps in-yun is also meant to convey that the film is not as simple as it seems, that it’s layered in unseen ways (which, I’m sure, is me misinterpreting the definition of in-yun but bear with me). That there’s depth between these two childhood friends (sweethearts?) and when they reconnect later in their lives, that connection has meaning beyond how it’s been set up in the film.

The QFS group was split on the strength of this connection. For some, the childhood connection between Na Young/Nora and Hae Sung didn’t suggest a deeper connection later in life. For example, Nora claims to not exactly remember the boys name while talking on the phone with her mother, but then discovers he’s been asking about her whereabouts for a little while now.

For others in our group, their connection in childhood was enough and felt familiar – this idea of two lives, connected through family, culture, and yes, love – two people diverging but when they reconnect, it’s fated they are to be together. Or, more specifically, in-yun. Case in point: your enjoyment of this film is directly related to whether or not you believe that their relationship at the beginning is strong enough that they could reconnect so quickly over such a long span of time.

Past Lives has the ease of a simple film well told but some of the trappings of a first-time filmmaker, several of us felt (including me). For example, there’s a scene where Nora’s (non-Korean) husband Arthur (John Magaro) talks about how they met and became a couple and moved in together and got married so she could get a green card, etc. What’s missing in his description is “love.” The kind of standard American relationship story devoid of cinematic spark or romance, but realistic and familiar. He continues to then say that in this version of the story, Hae Sun – the childhood lover – returns to her life and she realizes that this is who she should’ve been with her whole life. That he, Arthur, is the villain in this story. Hae Sun is more closely suited to her culturally but also very satisfying narratively. Both Nora and Arthur are writers so this aligns with their story-telling impulses.

Now, that’s all true but … we know that already as an audience. The filmmaker seemingly hasn’t trusted us to put that all together and she has a character explain it to us. This, to me, is a significant misstep in a story otherwise hewing close to cinematic realism. The scene, also, continues and Arthur says he started to learn Korean because Nora was talking in her sleep but in Korean. He says “You dream in a language I can’t understand. It’s like there’s this whole place inside you I can’t go.”

That is beautiful. It’s poetic, it speaks to the character himself, to their relationship, to the thrust and import of that scene. The scene could have very easily started here and it would have spoken volumes. But instead we get the needless explainer. And the ending as well – there’s a version of the film that ends as soon as Hae Sung leaves, wondering if this life is actually a past life and “we are already something else to each other in our next life? Who do you think we are then?”

Again – this is beautiful poetry. One member of the group suggested that ending of the film would be stronger if it ended right here, or right after this and he gets in his airport ride and goes. Instead of the long walk with Nora back to her husband where she cries. (And this is where I offered the additional criticism of staying in a wide shot instead of seeing her face here, for that felt like a payoff to me.) Even the opening shot - there’s an unseen bar patron watching the three in the bar. We push in slowly but instead of trusting the images of these three, with only their expressions and body language to inspire our curiosity, we’re hearing a bar patron who we will never see give us a setup that our eyes would have given us without the help.

Perhaps. These are all counterfactuals and there’s an argument in conducting film criticism that one needs to focus on the film in front of them and not the alternate version in our heads. Yes, valid – but still, the fact that these questions arise are less about how we would’ve done it differently and more about a few small weaknesses in an otherwise solid, simple film.

Despite some first-time filmmaker criticisms, there are a lot of beautiful uses of visual storytelling throughout - including the use of symmetry across eras between Na Young and Hae Sung.

And in defense of the simple film – I mean “simple” not that it lacks depth or intelligence. Quite the opposite. When the filmmaker has trusted us, we’ve filled in the blanks and walked in the shoes of two people different than ourselves and went on a journey with them. As one person in our group remarked – it’s refreshing to have a film that’s only about 90-minutes, has a simple but tender story, well-acted and executed, that brings up emotions in a natural way. Not overwrought or excessive or gratuitous. (Counterexamples from this award season include Oppenheimer, 2023 and Killer of the Flower Moon, 2023). I believed I added “inoffensive” as a way of describing Past Lives and, once again, I meant it as a compliment. There are no subplots, no side character, no stretching for meaning. It’s all there. Simple.

Whether that simplicity was effective or not, we all were in agreement, however, on this one thing – we are grateful that a movie like this is still being made, is receiving accolades, and that a lot of people have watched and enjoyed it. So consider this an endorsement of the simple film.

The Holdovers (2023)

QFS No. 133 - This is our first selection of an Alexander Payne film, one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers. I’ve seen nearly all of his films, hence its exclusion from the QFS Priority Selection List since I’ve seen nearly all of them. Truly one of the great living screenwriters, a modern auteur.

QFS No. 133 - The invitation for February 21, 2024

This is our first selection of an Alexander Payne film, one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers. I’ve seen nearly all of his movies, hence its exclusion from the QFS Priority Selection List since I’ve seen nearly all of them. Truly one of the great living screenwriters, a modern auteur.

The first Payne film I saw was Election (1999) at an advance screening in Ann Arbor* while I was in my first screenwriting class. Our professor took us to see it at the State Theater and the film didn’t even have the final credit scroll yet. I saw it a second time at the Michigan Theater during its regular release later that year and it remains one of my favorite viewing experiences – the film brought the house down, especially after one line in particular. Exemplary satire, Election is an underrated modern classic and should have earned Reese Witherspoon at least an Oscar nomination, one of a litany of Oscar Crimes™ over the years (see 2023: Gerwig, Greta).

Payne’s Sideways (2004) not only won him his first Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay but also single-handedly made Santa Barbara Wine Country overcrowded, drove up the demand for pinot noir production and consumption and destroyed the reputation of the perfectly fine merlot grape. His Nebraska (2015) is a beautiful, melancholic road trip film. Throw in About Schmidt (2002), and The Descendants (2011) for which he won another writing Oscar, and you could call that a pretty terrific career.

I’m sure I’m not the first one to suggest this, but from the way I see it Payne is the Preston Sturges of our times. Sturges, as you recall from QFS No. 2 The Miracle at Morgan Creek (1944), wrote and directed films about ordinary misfits caught in a lie or a deception – as a fake husband in The Miracle at Morgan Creek, Hail the Conquering Hero (1944) as a fake war hero or Sullivan’s Travels (1941) as a filmmaker posing as a fake hobo – as a way into the exploration of humanity, relationships and society. Both have a similar way of capturing a character’s story through humor, often bittersweet, but with the slightest of social commentary. With Sturges that commentary was a little more overt and daring, and Payne’s mission is not cultural or social criticism necessarily. But you can find it in his authentic portrayal of an ordinary person, his or her sense of normalcy upended.

Sturges might’ve used more sweet than bitter in his cinematic concoctions, and Payne can be acerbic and creates some truly uncomfortable and squirm-inducing scenes. So it’s not a perfect comparison but I stand by the assertion. Regardless, both carved out a particular niche in their eras – auteurs whose works relied upon well-told stories with grounded characters in exquisitely crafted scripts as opposed to artistic or visual innovation. With health doses of humor.

I’m very much looking forward to finally seeing another Alexander Payne film, his first in six years, and having a chance to discuss it with you. Please watch The Holdovers at home or in the theater – still playing somewhere near you I believe – and we’ll discuss!

*Home of the current National Champions of College Football.

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a moment in The Holdovers (2023) that feels like its heading towards familiar territory. A misunderstood curmudgeon teacher and his misfit students all have to somehow survive the winter together at their private boarding school as they’re stuck with each other until school resumes after the break. With this setup, it’s easy to be prepared for a story in which the students come to understand this man more and the teacher softens and becomes a better person and therefore a better teacher by knowing his students more personally – and everyone learns something about themselves or life that prepares them for the world more than their conventional education ever could.

I’m not trying to sound glib; many an excellent film has done this well and movingly – Dead Poets Society (1989) or The Breakfast Club (1985) come to mind. So that’s the direction Alexander Payne is appearing to veer us towards in The Holdovers.

But then, something happens. All the kids, except for one literally fly away in a helicopter to a mountain top.

What Payne really setting up for is this – don’t expect anything because this movie is not going where you think it is going.

As one of our group members put it, you think it’s going to be a movie about class, but it’s not just that; you think it’s going to be a movie a hardened grump falling in love and being transformed by that, but it’s not; you think it’s about the start of a friendship between a teacher and his student – it’s not that exactly either.

All of those themes are in The Holdovers, to be sure, but just when the narrative goes in the direction you think it’s going to go, it goes somewhere else. That this happened in a film that Alexander Payne directed but did not write – to me, that’s incredibly impressive. He took another script and made it a film that feels very much like his voice.

What Payne has always been good at is making characters feel real, even when they’re a little askew. His characters have believable inner lives, are imperfect, and struggle inwardly but not usually outwardly. What I’ve loved and appreciated about Payne’s movies is that they have a very distinct comedic edge but they’re truly dramas. I empathize with the characters in his movies because they seem so much like humans with familiar struggles.

The Holdovers caused me to experience something new for me in a Payne film – it made me well up with tears several times. Angus (Dominic Sessa) meets his father (Stephen Thorne) in a mental institution, they hug and Angus tells him he misses him. His father, seemingly moved, can actually only reply that he believes the institution’s staff is poisoning his food. And then you realize that Angus is truly alone and in deep need of love and encouragement. When Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) breaks down at the party about the loss of her son, you feel it deeply, as if she’s been holding it at bay for so long and finally lets her grief go.

Topping off all them, however, is the end. The handshake between Angus and Paul (Paul Giamatti). There is perhaps more power, more earned emotion in that handshake than in any number of romance films or romantic comedies’ climactic kisses. And importantly, it’s not a hug – it would’ve been ruined if it was a hug. It would’ve felt fake, like a movie. Because that’s not their relationship. They’re still teacher and student. They went through a journey together, learned each other’s deepest held secrets, have changed and grown to see each other as lonely, suffering, resilient human beings. And that handshake holds it all, with Paul’s cracking voice and Angus hearing from his teacher – a sort of surrogate father role – that the kid is going to be all right. That’s all Angus needed in his journey, was someone to tell him that. And it was earned, narratively, and paid off in the right way.

In the invitation to this week’s selection, I mentioned Payne as our era’s Preston Struges. And I think this film helps bolster that case. Let’s set aside how both auteurs deftly use comedy to tell a dramatic story in ways both narratively interesting but grounded in truth. There’s also the social criticisms embedded in their films.

Payne addresses class in The Holdovers in several ways but most importantly it’s woven into the DNA of the main character Paul. When we learn about his backstory, Paul reveals he was kicked out of Harvard because of allegations of plagiarism by the son of a famous person at Harvard – when it was actually the opposite, the son copied Paul’s work. But the administration wouldn’t have sided with a kid who left his abusive father and extricated himself from poverty and ended up at Harvard through his own means. The fact that he’s cut down by the wall of privilege is devastating in the retelling and is evident in the unresolved grief that Paul contains within.

Similarly, we hear about Mary’s late son who couldn’t get a scholarship to pay enough for college, went off to the army with the hopes of eventually going to college, only to have him die fighting in Vietnam. Mary’s story touches on race too – it’s never said but you know that he was the only Black kid in his class, whose mother worked there just so he could go to school and have a chance.

In all these ways, Payne is making an oblique criticism of the system that rewards the wealthy and well connected, but not through didactic speechifying, but through the story, through the setting, and through the characters. Simply pointing out it exists in the way it exists and portraying it in a way that shows it’s real and not a narrative contrivance is perhaps one of the best ways a filmmaker can illustrate how inequitable things truly are.

Sturges’ social criticisms of a different era centered around poverty and concepts of masculinity/military might. In Sullivan’s Travels (1945), Sullivan (Joel McCrea) a Hollywood director wants to make a movie about hobos. To do so, he goes and lives as one. But it’s skin deep – he can escape this any time so there’s no real lesson learned and he’s only doing this as a temporary means to an end. Through a series of circumstances, he ends up homeless and without memory and actually has to live as a vagrant. In both The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944, QFS No. 2) and Hail the Conquering Hero (1944), the main character has to pose as a military man or a masculine husband figure despite being just an ordinary guy who gets caught up in a… well not quite lies, but untruths let’s say.

(Above) Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels on the left (1944) and Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers on the right. Completely different storylines in these specific films, but both filmmakers auteurs wield comedy to tell dramatic stories with an embedded criticism of class. Auteurs of their times.

Sturges uses more narrative contrivances than Payne does but both point out some of the unfairness or absurdity of life through a lived experience of a character, through the use of humor and poignancy – with near perfect writing and performances. Again, it’s not a perfect comparison but both Payne and Sturges were auteurs who had something to say about our current world and about humanity that is revealing while simultaneously being entertaining.

Another member of the group put it this way – I thank the film gods that a movie like The Holdovers is still being made. Writing, directing, acting, an adult storyline and grown-up themes. This is the film that has become an endangered species in the era of limited series and the mid-budget character driven dramas ending up on screening services instead of movie screens. Thank the film gods indeed for giving us Dominic Sessa and Da’Vine Joy Randolph in these roles, and for seeing Paul Giamatti corner the market on the curmudgeon with the soft center. And thank the film gods for Alexander Payne continuing to use his formidable might to bring these stories to life.

A Night at the Opera (1935)

QFS No. 132 - Okay fine, so it’s not exactly a holiday classic, but doesn’t this time of year seem like a perfect opportunity to watch a Marx Brothers film? We haven’t yet selected a film by the comedy legends, and A Night at the Opera (1935) is widely known as one of their best films.

QFS No. 132 - The invitation for December 20, 2023

For our final 2023 selection, we’re going to a holiday classic!

Okay fine, so it’s not exactly a holiday classic, but doesn’t this time of year seem like a perfect opportunity to watch a Marx Brothers film? We haven’t yet selected a film by the comedy legends, and A Night at the Opera is widely known as one of their best films.

I know I’ve seen parts of many of their movies, but I believe I’ve only seen Duck Soup (1933) from start to finish. I have a feeling the redeeming artistic value of this movie might be minimal. But movies are a lot of things – and sometimes they’re just pure entertainment. Comedies are difficult and require so much technical skill, so it should be fun to take a closer look at how they pull of the perfect banana cream pie toss.

And with the holiday break and kids are off of school, this might be a fun one to watch with them for all the gags and mayhem and the answer to difficult trivia questions. For example – can you name all of the Marx Brothers? I got three out of five (answers below)*.

So join us for the final QFS of 2023. I’d love to do more before the calendar turns, but wouldn’t you know it? The strike ended and now there is finally directing work. It’s back to the TV mill for me, hence there will be some pauses coming up for the movie group.

Enjoy A Night at the Opera as we wrap up QFS for 2023!

*Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo and Zeppo. I totally missed Chico and Gummo, in part because Gummo was not in any movies. I have no excuse for missing Chico.

Reactions and Analyses:

Comedy doesn’t always transcend eras. Some can be very specific to the time in which it was created, with cultural references or styles of speaking that become outdated. The Marx Brothers are among those who have managed to create works of comedy that endures beyond their lifetimes.

True, in A Night at the Opera (1935), there are minor handful of contemporary jokes lost on modern audiences. But even in those – such as the one about “quintuplets up in Canada” – the content of the joke itself may not have lasted, but the delivery and Otis B. Driftwood (Groucho Marx)’s reaction and delivery of the line still gets a laugh: “Well, I wouldn't know about that; I haven't been in Canada in years.”

Any discussion about A Night of the Opera is going to center on the Marx Brothers, of course, because when you get down to it, that’s really primarily what the movie is – a launching point for their comedy. Much of our discussion was about the brothers and almost no talk about the plot or the filmmaking. Which is the point; it is, after all, a Marx Brothers movie.

In addition to Groucho’s near-perfect, constant one-liner deliveries, the Marx Brothers are simply the greatest agents of chaos in movie history. Throw them into any situation, and that’s what you get – chaos. That’s the hallmark of a Marx Brothers movie. The difference, perhaps, in this film is with the inclusion of some musical numbers, the attempt at a love story, and only minor social commentary (as opposed to the more direct commentary in Duck Soup, 1933)

Several QFS members pointed out how one can see their influence on future comedians - Martin Short came to mind, the magic of Penn and Teller, and even Mel Brooks. Rodney Dangerfield is the clearest heir to Groucho Marx we could think of and the discovery of that delighted me immensely.

One QFSer felt less sanguine about the film, that it was repetitive and there wasn’t a story – as compared to a Charlie Chaplin film, for example. Chaplin’s films, though often featuring the same Tramp character, had a strong storyline, a social commentary, pathos, and of course groundbreaking visual comedy and sight gags. Marx Brothers movies, however, were merely a way to setup the Marx Brothers wreaking havoc in a straight world around them. Both are funny, both have endured, and both have stood the test of time. Where Chaplin used artistry to enhance his comedy, the Marx Brothers relied on their on-screen personas and vaudevillian skills to enhance theirs.

One way of thinking about this, to me, is there are movies that are funny (Chaplin’s Modern Times, 1936) and there are funny movies (A Night at the Opera). Movies that are funny are films with a compelling driving narrative that’s told in a funny and artful way. Funny movies are comedies that favor humor and gags above the plot and storyline. This is an utterly unsophisticated way of putting this, but a distinction between styles of films that make audiences laugh is worth considering. How do you make someone laugh? There’s no one way and the differences between how Chaplain does it and the Marx Brothers do it provide some insight into that. A deep dive into this comedy would be, of course, a lot of fun.

Generally speaking, the group agreed that though the plot was thin and perhaps unnecessary even, this is a film that you can probably just pick up at any point and simply enjoy the gags – the absurd amount of people in the cabin, the disappearing beds, the contract negotiation, the final opera, and so on. Perhaps a funny movie doesn’t need to be much more than that.

Black Narcissus (1947)

QFS No. 131 - Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell are the powerhouse directing duo from England whose legendary work includes The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), 49th Parallel (1941), The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and of course this week’s selection The Black Narcissus. I’ve only scratched the surface myself with their career work but everything I’ve seen has been incredibly impressive.

QFS No. 131 - The invitation for December 13, 2023

Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell are the powerhouse directing duo from England whose legendary work includes The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), 49th Parallel (1941) with Laurence Olivier, The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and of course this week’s selection The Black Narcissus. I’ve only scratched the surface myself with their career work but everything I’ve seen has been incredibly impressive. It’s no wonder they are so influential to the following generation of filmmakers – Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee to name two – and I feel they need to be studied further by us and future filmmakers.

One of the hallmarks of Pressburger and Powell is their masterly grasp of film craft. The cinematography in their films is legendary and was duly awarded throughout their careers. Their art direction, costumes and set design are unforgettable. I point you to The Red Shoes for a textbook in the complementary usof all those elements as a case in point. Their numerous Oscar nominations for screenwriting and several for editing illustrate their excellence in storytelling for the visual medium.